This Isn’t an Immigration Crisis. It’s an Imperial Hangover

The consequences of empire don’t stop at the border

We’ve heard it all before. The talking heads on Fox scream that we're "being invaded". Or the red caps at Trump rallies complaining that "they're taking our jobs". Or the felon-in-chief complaining that Mexico, "isn't sending their best". America talks about immigration like it’s a surprise. As if millions of brown folks just decided randomly to march their way up to the border and "take over".

But migration doesn’t just manifest out of thin air. People don’t abandon their homes, families, and histories because they feel adventurous. They do it because something pushed them out. Something broke. And more often than not, that “something” has red, white, and blue fingerprints all over it.

What we're seeing isn't an immigration crisis. It’s the hangover from a century of coups, corporate exploitation, economic sabotage, and foreign policy carried out at gunpoint and with briefcases full of cash. The U.S. spent decades destabilizing Latin America, then turned around and built a wall to keep the fallout contained.

We’re not being “invaded.” We’re waking up to the consequences of power we never questioned.

Before we look at the aftermath, we have to understand the design.

The United States didn’t stumble into these disasters. It didn’t just have a few bad decades or make some regrettable decisions. What happened in Latin America, and what’s still happening, wasn’t policy gone wrong.

It was policy working exactly as intended.

A Pattern, Not a Policy

When you look at US foreign policy in Latin America, the pattern is painfully obvious. What started in the 17th century as a shield against expanding European colonialism, became an excuse for unchecked American imperialism. This evolved several times, and bit us in the ass a few more, as it’s doing again today.

The Myth of the Monroe Doctrine

In 1823, President James Monroe stood before Congress and declared, “the American continents… are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” It sounded like a bold, principled defense of Latin American independence. The U.S. was casting itself as a guardian, warning old empires to stay out of the Western Hemisphere.

But the reality wasn’t so noble.

At the time, the U.S. had no navy, no real army, and no ability to enforce such a threat. The doctrine was rhetorical cover: a flag planted without the muscle to back it up. In practice, it was the British Navy, not American power, that kept Spain and France at bay.

And crucially, the Monroe Doctrine wasn’t treated as binding U.S. foreign policy until decades later, when it suddenly aligned with American commercial and strategic interests in Latin America.

By the time the U.S. started enforcing it in the late 19th century, the doctrine had morphed from a passive warning into an active claim of regional ownership. Countless European incursions had gone unanswered—but now, any threat to American influence would be met with force.

From Pretext to Practice

By the early 1900s, the Monroe Doctrine had a new interpretation, thanks to Theodore Roosevelt. His Roosevelt Corollary declared that the United States had the right to intervene in Latin American countries to maintain “stability” and prevent “chronic wrongdoing.” In reality, it became a license for invasion, occupation, and regime change wherever U.S. interests were at stake.

You can see where this is headed.

Cuba, 1901: After the Spanish-American War, the U.S. forced the Platt Amendment onto Cuba’s new constitution. This gave the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuban affairs at will. It claimed to protect Cuban independence, but really served U.S. sugar barons. America intervened again in 1906, 1912, and 1917—each time under the guise of restoring order.

Panama, 1903: Roosevelt sent U.S. warships to blockade Colombian sea lanes, helping Panamanian rebels win independence. Within days, the U.S. recognized Panama, and locked in the rights to build and control the Panama Canal.

Nicaragua, 1912–1933: U.S. Marines invaded to protect American railroad and banking interests. When civil war broke out again in 1926, they returned—this time staying until 1933. Both occupations helped secure U.S.-friendly regimes and crushed nationalist resistance.

Mexico, 1914: During the Mexican Revolution, the U.S. seized the port of Veracruz to influence the outcome of the conflict. It was a major escalation and nearly led to full-scale war.

Haiti, 1915–1934: The U.S. invaded after political unrest and ruled Haiti under martial law for nearly 20 years. American forces imposed forced labor, rewrote the constitution to allow foreign land ownership, and brutally suppressed resistance.

Dominican Republic, 1916–1924: Another U.S. military government, another occupation to “restore order.” The U.S. took control of customs, finances, and police, entrenching elite rule and dependency.

By the time the 20th century hit its stride, the mask was off. The Monroe Doctrine was no longer a promise to keep colonizers out. It was a blueprint for becoming one. The U.S. didn’t just fend off European empires. It stepped into their place. With Marines instead of monarchs. With bankers instead of viceroys. With “stability” as the rallying cry and corporate interest as the compass.

And the consequences didn’t stay buried in the past. They’re still walking north.

The Receipts Are in the Ruins

You don’t need a declassified memo to understand what happened. The evidence is public, bloody, and at times, celebrated as foreign policy success.

If we want to understand why people are fleeing their homes, we have to ask: what did we do to those homes?

The receipts aren’t hidden. They’re scattered across the hemisphere. Here are just a few, from the past hundred years.

Guatemala - 1954

What happened: The CIA overthrew democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz for trying to redistribute land (including unused land owned by United Fruit Company).

Why it matters: Sparked decades of civil war, genocide against Indigenous people, and ongoing instability that’s still driving migration today.

Consequence:

- Estimated number of unauthorized Guatemalan immigrants: ~725k

- Number of Guatemalan immigrants in TPS (or eligible for TPS): ~662k

El Salvador - 1980's

What happened: U.S. poured billions into El Salvador’s right-wing military during a brutal civil war, training forces responsible for massacres (e.g., El Mozote).

Why it matters: The U.S. fueled a brutal civil war that displaced thousands, pushing waves of refugees into cities like Los Angeles. There, many young Salvadorans formed gangs for protection, including what would become MS-13. Later, the U.S. deported them back to a shattered El Salvador, exporting the violence we helped create in a new form.

Consequence:

- Estimated number of unauthorized Salvadoran immigrants: ~741k

- Number of Salvadorans under TPS: ~250k

Nicaragua - 1980's

What happened: The U.S. funded and armed the Contras, a right-wing militia fighting the leftist Sandinista government.

Why it matters: The Contras committed widespread atrocities, including torture, rape, assassinations of civilians, and attacks on schools, clinics, and infrastructure

U.S. role: Direct CIA training and funding, despite Congress attempting to cut it off, which led to the Iran-Contra scandal. Reagan called them “the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers.”

Consequence:

- Estimated number of unauthorized Nicaraguan immigrants: ~100k

- Nicaraguan immigrants on Humanitarian parole: ~96k

- Nicaraguan immigrants in TPS program: ~200k

Personal note: In 1988, my father was among a group indicted in Miami under the Neutrality Act of 1794 for recruiting personnel, arranging arms shipments, and supporting Contra operations in Nicaragua: activities federal prosecutors said mirrored CIA covert missions that Congress had banned via the Boland Amendment. While he was not a policymaker, he was effectively working in parallel with the official U.S. strategy, moving weapons and personnel into Honduras and Nicaragua. The charges weren't about ideological dissent, they were about denying official accountability. His prosecution served as a tool to obscure the fact that these operations were happening, with or without formal approval.

Honduras – 1980s

What happened: Throughout the 1980s, Honduras became a key staging ground for U.S. operations in Central America, especially the Contra war against Nicaragua. The U.S. provided hundreds of millions in military aid and used Honduras as a base for training and launching anti-leftist forces, while turning a blind eye to local repression.

Why it matters: U.S.-backed Honduran military units (e.g., Battalion 3-16) were responsible for torture, disappearances, and assassinations of journalists, students, and activists. The country’s fragile institutions never recovered. Corruption, cartel infiltration, and political instability deepened over time. This ongoing instability and violence has driven consistent migration north.

Consequence:

- Estimated number of unauthorized Honduran immigrants in the U.S.: ~556,000

- Hondurans granted CHNV Humanitarian Parole (2023–2024): ~90,000+

Haiti - 2004

What happened: In 2004, U.S. forces kidnapped and forcibly removed Haiti’s democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, putting him on a U.S. military plane and flying him to exile in Africa. The Bush administration denied it was a coup. Aristide called it a “modern-day kidnapping.”

Why it matters: Aristide had pushed for debt relief, higher wages, and the prosecution of human rights violators from previous regimes, which threatened elite and foreign interests. His removal plunged Haiti into deep political chaos, opened the door for criminal gangs to gain power, and further collapsed basic infrastructure. Today’s Haitian migration crisis didn’t start with the 2010 earthquake. It started with U.S.-engineered political collapse.

U.S. role: Backroom diplomacy turned armed extraction. Washington denied responsibility, but enabled the vacuum that Haitians are still fleeing.

Consequence:

- Estimated number of unauthorized Haitian immigrants: ~115k

- Haitians in TPS program: ~512k

- Haitians under Humanitarian parole: ~214k

Destabilization by Design

U.S. involvement in Latin America wasn’t a series of isolated missteps. It was a system. A repeatable model. Destabilize a country under the banner of freedom or free markets, prop up a friendly regime, and crack open the economy for American corporations. When things got messy, the fallout was labeled a local problem. But these weren’t accidents. They were blueprints with blood on them, refined over decades, from Marines to multinational banks, from coups to coercive trade deals. The empire didn’t just act. It engineered dependency.

The Playbook

If you step back far enough, the chaos looks suspiciously consistent. These weren’t blunders. They were steps in a process that was tested, repeated, and refined across borders and decades. U.S. foreign policy in Latin America followed a pattern so familiar it may as well have been printed on White House letterhead.

1. Destabilize

The first step is simple: turn reform into a threat. It didn’t matter if the government in question was democratically elected. If it talked about land reform, nationalizing resources, or even taxing foreign companies, Washington rang the alarm. “Communism” became the magic word. It didn’t have to be true. It just had to be loud enough to justify action.

Árbenz in Guatemala wanted to redistribute idle land held by United Fruit. Allende in Chile proposed nationalizing copper. Both were painted as Marxist threats to the hemisphere, and both were targeted for removal.

2. Intervene

Once the target was branded, the U.S. moved in: often quietly, sometimes with boots. CIA coups, military advisors, paramilitary funding, or flat-out invasions were all fair game. The goal wasn’t just regime change. It was narrative control. The United States posed as liberator even while toppling leaders chosen by their own people.

These interventions were surgical in the beginning, then brutal in the cleanup. In El Salvador and Nicaragua, the U.S. trained death squads and Contra rebels to “combat communism.” In practice, it meant villages razed, activists murdered, and generations traumatized.

3. Restructure

With the threat removed, it was time to rebuild, on U.S. terms. New leaders, often trained in U.S. military academies or bankrolled by American interests, were installed with one job: open the economy. That meant slashing social programs, privatizing national industries, and inviting in foreign capital under “free market” reforms.

The IMF and World Bank arrived with glossy brochures and knives. Their loans came with conditions: cut subsidies, lower tariffs, let Western corporations in. For countries still bleeding from civil wars and coups, it was economic shock therapy, with no anesthesia.

4. Extract

This is where the real payoff came in. With barriers dismantled, U.S. companies swooped in. Mining rights, agribusiness contracts, oil concessions, all at fire-sale prices. Labor was cheap, oversight nonexistent, and local resistance easily branded as insurgency.

Latin America became a buffet line for American capital. And when locals pushed back, through protest, elections, or revolution, they were simply plugged back into step one. The cycle restarted.

The Monsters We Made

You can only light so many fires before the smoke comes back for you.

The United States spent the better part of a century destabilizing Latin America. Dismantling governments, financing violence, and reshaping economies for profit. But the chaos we created didn’t stay directionless forever. In many places, it hardened into regimes. Some brutal, some populist, some both. They rose from the ashes of American intervention. They didn’t just emerge despite U.S. involvement. They emerged because of it.

Cuba: When Corruption Became Revolution

Before Fidel Castro, there was Fulgencio Batista. A military dictator backed and armed by the U.S., beloved by the mob, and friendly to American sugar and hotel interests. Cuba, for decades, functioned like a casino colony: cheap labor, cheap women, and guaranteed profits. When Cubans revolted, it wasn’t because they were dreaming of Marx, it was because they were choking on the smoke of U.S.-backed exploitation. Castro didn’t rise in a vacuum. He rose in a vacuum we helped create.

Nicaragua: From Somoza to Sandino to Strongman

The Somoza dynasty, propped up by U.S. arms and money, ran Nicaragua like a family business for decades. When the Sandinistas overthrew them in 1979, it wasn’t a communist invasion. It was a backlash. The U.S. responded by funding the Contras. This led to the Iran-Contra scandal, the militarization of the countryside, and eventually… another strongman: Daniel Ortega. Once a revolutionary, now a dictator in his own right. And we helped write every chapter of that arc.

Venezuela: When Populism Became Collapse

Long before Hugo Chávez became a symbol of anti-Americanism, Venezuela was a darling of U.S. oil interests. For most of the 20th century, the country’s wealth was siphoned by foreign corporations and domestic elites while the majority remained in poverty. Chávez, flawed, bombastic, and authoritarian, rose on the promise of equity and national dignity. But U.S. hostility only hardened his grip. Sanctions, attempted coups, and diplomatic isolation fed his paranoia and weakened civil society. By the time Nicolás Maduro took over, the system was already collapsing under its own contradictions, and the people were once again fleeing the fallout.

These regimes aren’t heroic. They’re not models. They’re symptoms. And we helped create the infection.

When Americans ask why so many migrants come from “failed states,” the answer isn’t just corruption or socialism or gang violence. The answer, more often than not, starts with our flag.

Nuestra America

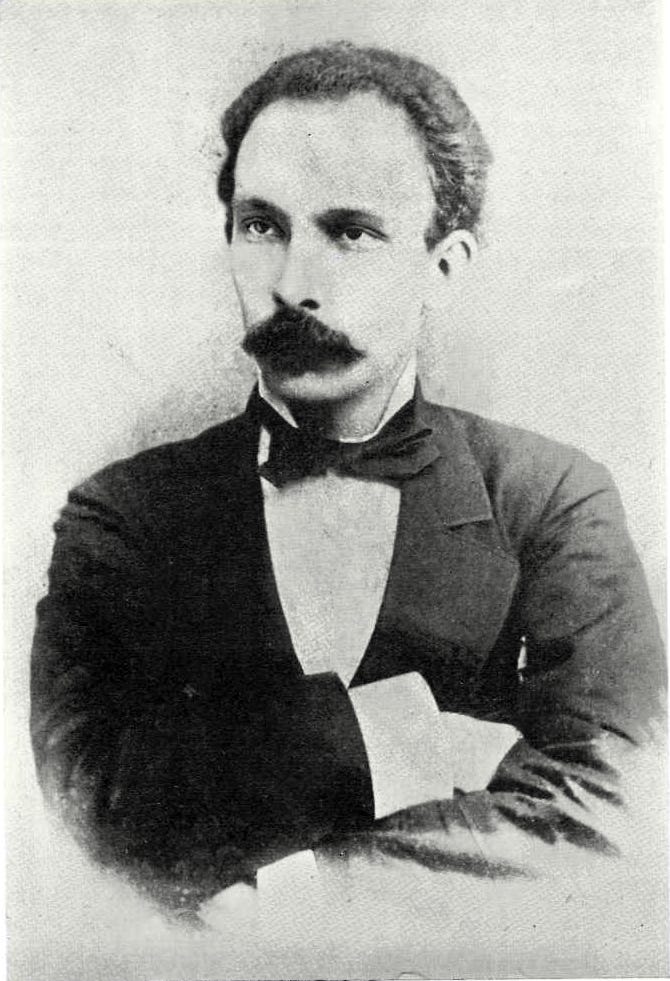

Before the gunboats. Before the coups. Before sugar barons became statesmen and revolutions were born in the rubble, José Martí tried to warn us.

In his 1891 essay Nuestra América, Martí laid out a vision for Latin America that was fiercely independent. Not just from European empires, but from the rising ambitions of the United States. He called for governments built on local realities, not foreign ideologies. For leaders who knew their land, their people, their languages. Not imported elites mimicking Paris or Washington.

To Martí, dependence was the true danger. Not just military occupation, but intellectual and cultural colonization. He saw the United States as a nation both powerful and arrogant, one that might cloak its ambition in liberty but act out of appetite.

“The scorn of our formidable neighbor, who does not know us, is our America’s greatest danger.”

He wrote those words before the Platt Amendment. Before the occupation of Haiti. Before the CIA learned Spanish. And still, he nailed it.

Martí didn’t want Latin America to be a victim or a mirror. He wanted it to be itself. To “govern itself with that original creative spirit which makes a people great and free.” But that dream was quickly buried beneath decades of U.S. interventions and puppet regimes. His warnings weren’t just ignored, they were trampled by history, paved over with landing strips and debt agreements.

“It is imperative that the government of the village be constructed with the elements of the village. The foolish are those who derive their ideas from books written by alien thinkers.”

Martí was not a socialist. Not a revolutionary in the modern sense. He was a poet, a fighter, and a visionary who believed freedom must come from within, not be installed from abroad or stolen under cover of stability. His ghost haunts every country we touched. Not because he failed, but because we did.

Today, when migrants knock on our door, fleeing the wreckage we helped engineer, Martí’s voice still echoes:

"These countries will either be made of their own soul—or they will be broken trying."

The Morning After Empire

Empires rarely end with a bang. They erode. They rot from the inside, even as they still cast a long shadow. And sometimes, they wake up with a hangover. Head pounding, vision blurred, unable to remember who ordered the last round.

That’s where we are.

We’re not watching an “immigration crisis.” We’re living through the aftershocks of empire. The headlines scream about caravans, about crime, about the “invasion.” But they never mention the coups, the sanctions, the paramilitary training, the debt traps, the trade deals written in English and enforced with dollars. They never mention the flags planted, the land grabbed, the dictators armed, the families broken.

And they definitely never mention why these people are coming. Because the real answer is inconvenient:

They’re not invading us. They’re escaping us.

They are the fallout. The side effects. The receipts.

And now we are waking up to the uncomfortable truth that all those decades of foreign policy, all those "interventions" and "investments" and "protections," were never free. The bill has come due. And the people bearing it aren’t invaders. They’re survivors.

This is the morning after. The noise is quieter now, but the damage is done. The question isn’t whether we’ll pay for what we did.

The question is whether we’ll finally admit that we did it.

100% correct