A Republic, If You Can Keep It

Independence means nothing if we won't defend it.

"When the mob and the press and the whole world tell you to move, your job is to plant yourself like a tree beside the river of truth, and tell the whole world: 'No, you move.'"

This line from a Captain America comic (originally taken from Mark Twain) cuts deeper than most political speeches you'll hear this July 4th. It captures something essential about moral courage that we've abandoned for something easier: the performance of righteousness without the cost of actual principle.

This year marks 249 years since the Declaration of Independence. One year away from a quarter-millennium. If we reach July 4th, 2026, we will stand as one of the longest-continuously operating constitutional democracies in the modern world, a rare endurance in a history littered with failed republics.

But that's a very big "if."

Walk through any July 4th celebration and you'll see the performance everywhere. Flags on trucks that have never carried anything heavier than groceries. Military tributes from people who've never voted for veteran healthcare funding. Constitution worship from those who would ignore the rights of others while shouting about their own.

But the founders who created this holiday understood something different about American identity. When King George's government and the colonial press demanded submission, when friends and neighbors called them traitors, when the cost of resistance meant losing everything they had built, they planted their feet and said no.

Their courage wasn't cultural or tribal. It was constitutional. They weren't defending American customs or traditions because there weren't any yet. They were defending principles they believed were universal: that government derives its power from the consent of the governed, that rights come from nature rather than authority, that no one should live under laws they had no hand in making.

What would they say about our moment? What would make them plant their feet and refuse to budge today? Thomas Paine warned, "The strength and power of despotism consists wholly in the fear of resistance." What the powerful fear most is not violence. It is defiance. It is a population that refuses to yield, even when outnumbered, outspent, and pushed to the margins.

When the Founders Faced the Mob

George Washington's greatest act of courage wasn't on any battlefield. It happened in a quiet room at Fraunces Tavern in December 1783. The war was over. The British had evacuated New York. Victory had been won.

Washington gathered his officers there to say goodbye. After eight years of war, he stood before men who would have followed him anywhere, including, if he had wanted it, into power. Some had urged him to take control, to become a stabilizing monarch or dictator to prevent the young republic from fracturing.

Instead, he resigned. He thanked them. He wept. And then he handed power back to the people.

It was a moment so unprecedented, King George III is said to have called Washington the greatest man alive for walking away from absolute power. Washington's action at Fraunces Tavern echoed louder than any cannon blast: the commander-in-chief of a victorious army bowed to civilian government. And then he went home.

Washington listened to their arguments, then quietly told them they had fought a war to escape kings, not create new ones. He walked away from ultimate power not once but twice, setting a precedent that has held for almost 250 years.

In his Farewell Address, he warned against exactly what we see today: "Guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism." He knew that democracy's greatest enemies would wrap themselves in its symbols while gutting its substance.

Washington would look at politicians who invoke his name while concentrating power in executive agencies, who bypass Congress through emergency declarations, who treat constitutional limits as suggestions rather than law, and he would recognize the very tyranny he refused to become.

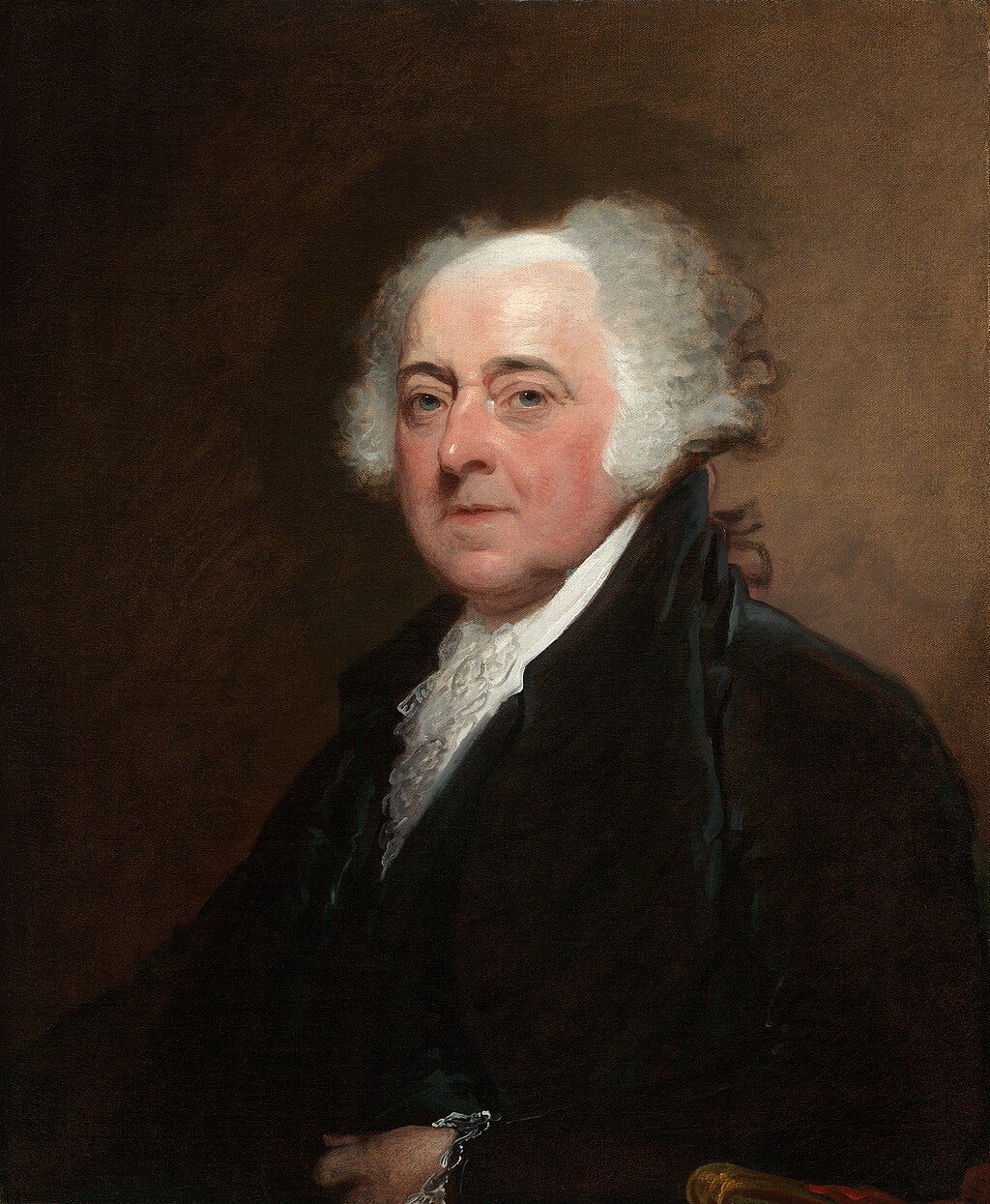

John Adams understood that democracy requires something more than good intentions. "Remember, democracy never lasts long," he wrote. "It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide."

Adams saw democracy's fatal flaw: the tendency of citizens to choose leaders who tell them what they want to hear rather than what they need to know. He warned against demagogues who would flatter the masses while pursuing their own aggrandizement.

He would recognize today's political theater immediately. Politicians who promise simple solutions to complex problems. Leaders who treat governing like entertainment, who prefer rallies to policy briefings, who measure success by crowd size rather than legislative achievement.

Adams would plant himself firmly against the cult of personality that has infected American politics, regardless of which personality is being worshiped.

Benjamin Franklin spent the Constitutional Convention's final day watching delegates sign the document that would create our government. Looking at the chair where Washington had presided, Franklin noticed that its back was decorated with a half-sun. He said, "I have often looked at that sun behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting. But now I know that it is a rising sun."

Franklin believed in America's potential, but he also understood how easily that potential could be wasted. When asked what kind of government the Convention had created, he replied: "A republic, if you can keep it."

The "if" was crucial. Franklin knew that republics don't sustain themselves. Now, 249 years later, we're facing the ultimate test of that "if." We're one year away from reaching 250 years as a constitutional democracy. Very few republics in history have lasted this long without collapsing, transforming into something else, or descending into authoritarianism. Most die much younger.

They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.

Ben Franklin

Franklin would look at Americans who treat politics like spectator sports, who choose representatives based on entertainment value rather than competence, who prefer outrage to understanding, and he would ask the same question he asked in 1787: Can you keep it? Not forever. Just for one more year. Just long enough to reach that 250th birthday.

Then we can ask the question again.

What They Would Recognize Today

The founders created a system of checks and balances because they understood that power corrupts even well-intentioned people. They divided authority between branches, between federal and state governments, between majority rule and minority rights. They made the system deliberately inefficient because they feared efficient tyranny more than inefficient democracy.

Today, the most urgent threats to those safeguards come from a systematic erosion of constitutional norms and accountability. We've seen a breakdown of checks and balances, a steady rise in executive overreach, and open plans for government-led retribution. Political leaders increasingly act with impunity, sanctioning illegal detentions and family separations, undermining judicial independence, and encouraging the weaponization of federal agencies for partisan gain. The Republican Party has largely enabled or encouraged these shifts, while the Democratic Party has proven ineffective at meaningfully resisting them. These developments aren’t isolated missteps. They represent a pattern of normalized violations of civil rights and democratic process. The founders would not only recognize this slide toward tyranny; they would demand its reversal.

They would see politicians who campaign against Washington while centralizing more power there. They would watch as emergency powers become permanent, as constitutional crises become routine, as checks and balances become mere suggestions when they conflict with political expedience.

The founders designed the system to make dramatic change difficult precisely because they understood how quickly popular movements could destroy democratic institutions. They would be appalled by leaders who treat constitutional limits as obstacles to overcome rather than principles to uphold.

They created a federalist system because they believed that local governments, closer to the people, would be more responsive and accountable than distant bureaucracies. Today, Washington wants to decide everything from school curriculum to bathroom policies, expanding its reach into areas once handled by communities and states, while local officials deflect responsibility by blaming federal mandates for their own failures to govern.

The founders would see this centralization as exactly the kind of distant, unaccountable government they fought a revolution to escape.

Perhaps most importantly, they would recognize how American political discourse has abandoned the possibility of persuasion through reason. The founders were products of the Enlightenment. They believed that rational people, presented with evidence and argument, could reach reasonable conclusions about shared problems.

Today's political culture assumes the opposite: that opponents are acting in bad faith, that evidence is irrelevant, that the only choice is between total victory and total defeat. Politicians don't debate policy; they perform grievance. Citizens don't engage with arguments; they signal tribal loyalty.

The founders would see this as the death of republican government, which requires citizens capable of reasoning together about the common good.

Planting Yourself Beside Truth

What would it mean to follow the founders' example today? What would it look like to plant yourself like a tree beside the river of truth when the mob demands you move?

It would mean recognizing that the system has already failed in many places, that the usual channels have been corrupted, co-opted, or gutted. That the courts no longer check power, that elections are manipulated by gerrymandering and disinformation, and that laws are enforced based on loyalty, not justice. And despite all of that, it would mean refusing to surrender the ground we have left.

It means showing up in person, not just online. It means putting your body in places where injustice is being carried out: in boardrooms, in courtrooms, in the streets. It means standing your physical ground when books are banned, when families are separated by government order, when state violence is used to crush dissent. It means knowing that you might lose something, your comfort, your job, your safety, and doing it anyway.

It means not just voting, but organizing. Not just speaking, but acting. And not just appealing to authority, but challenging it when it betrays the people it's meant to serve. The founders didn’t wait for permission. They took action. Sometimes, so must we.

This isn’t a call to violence. It’s a call to refusal. A call to obstruction. A call to defiance rooted in principle, not party. A call to reclaim the physical, moral, and civic space that has been abandoned out of fear or fatigue.

The tree doesn’t move because it’s convenient. It doesn’t move because the wind says so. It stays rooted because that’s where the truth is. And if you’re not willing to be rooted, to be immovable in defense of what matters, then don’t call yourself a patriot.

This is what it means now: not just holding beliefs, but holding the line.

The Choice

The mob of our time operates differently than the one the founders faced, but its essential demand remains the same: abandon inconvenient principles for comfortable conformity. Choose your tribe over your conscience. Pick a side and defend it regardless of evidence.

The river of truth offers something different: the possibility that constitutional principles can transcend partisan politics, that evidence can matter more than ideology, that democratic institutions can survive the people who temporarily control them.

This isn't about finding some imaginary middle ground between extremes. It's about identifying principles worth defending and defending them consistently, even when consistency costs something.

We stand at year 249 of an unprecedented experiment in human self-governance. In one year, we could celebrate a rare milestone as one of the longest-sustaining constitutional democracies in the modern world. Or we could join the graveyard of republics that couldn't survive their own success, their own prosperity, their own freedom.

The founders weren't motivated by cultural nostalgia or tribal identity. They were building something that had never existed before: a government that derived its authority from the consent of rational citizens capable of self-governance. They understood that this experiment could fail, that it required constant vigilance, that each generation would face its own test of whether republican government could survive contact with human nature.

Our test isn't foreign invasion or economic collapse. It's whether Americans can remember why constitutional principles matter more than political victories, why democratic processes matter more than satisfying outcomes, why protecting rights for everyone matters more than protecting privileges for our allies.

At 249 years, the American republic has become something the founders could barely imagine: a continental democracy of over 330 million people from every corner of the earth, bound together by ideas rather than blood or soil. The scale alone makes their constitutional framework remarkable. Whether it can survive its own success remains an open question.

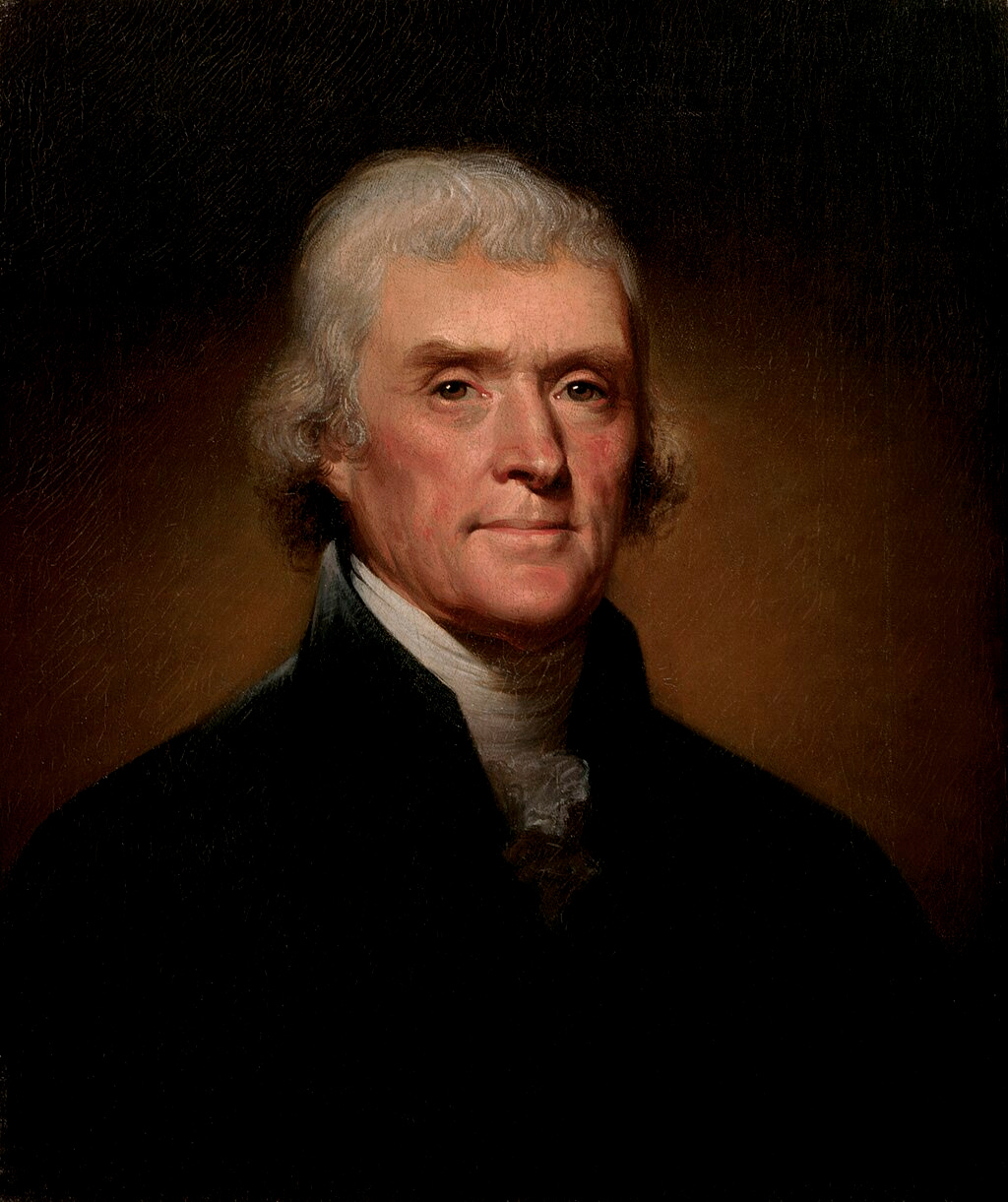

The founders faced their moment of testing and chose principle over comfort, law over power, the difficult right over the easy wrong. As Jefferson once warned, "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants." He did not celebrate violence, but he understood a hard truth: freedom has a cost, and it is paid most often when compromise is no longer an option. They planted themselves beside truths that powerful people wanted suppressed and told the world they would not be moved.

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.

Thomas Jefferson

Today, when politicians demand that you abandon constitutional limits for political expediency, when movements insist that you choose tribal loyalty over individual rights, when the mob demands that you move from inconvenient principles to comfortable lies, you face the same choice they faced.

Will you plant yourself like a tree beside the river of truth? Will you stand your ground when those in power strip away rights and silence dissent, knowing that the usual paths of redress are failing us? Will you be ready to defend what's left of this republic when the moment for polite protest has passed and the consequences for resistance grow sharper by the day?

The founders left us their answer in the form of a Constitution, a republic, and a challenge. We've kept it for 249 years. The question is whether we have the courage to reach that historic 250th anniversary and beyond.

This July 4th, remember that patriotism isn't performance. It's principle. And principle, as the founders understood, sometimes requires you to stand alone and tell the world: "No, you move."

We are 365 days away from a milestone birthday, or a funeral procession for the republic. One year from now, we will either mark a quarter-millennium of self-rule, or witness the final gasp of a system too hollowed out to endure. The choice is ours.

Originally published July 4, 2025